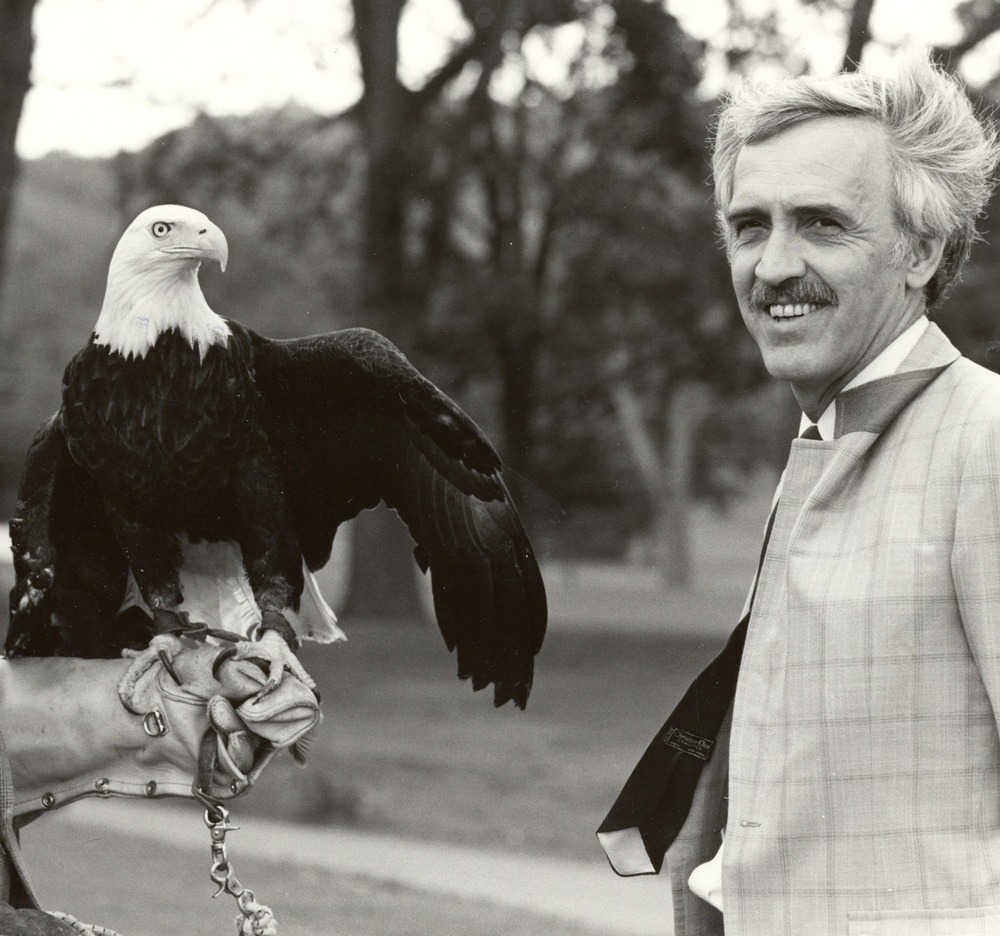

As the Tennessee Conservation League’s first employee—and the executive director of the organization for 23 years—Tony Campbell set the groundwork for what would become the Tennessee Wildlife Federation.

Under Tony Campbell’s leadership, the Tennessee Conservation League became a force on behalf of wildlife and habitat.

As executive director of the Tennessee Conservation League (TCL) for 23 of perhaps the most formative years of wildlife conservation in the state’s history, Tony Campbell’s handprints can be found on everything from wetlands acquisition to the structure of the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency (TWRA) to even the placement of our state’s roadways. He was TCL’s first staff person, a dogged trailblazer for the interests of both wildlife and sportsmen on Capital Hill, and firmly placed the organization that would become the Tennessee Wildlife Federation into the public consciousness.

And oddly enough, it could be argued that the success story of our wild things and places in Tennessee over the latter part of the 20th century was directly related to the mild climate of Las Cruces, N.M., the boy/girl ratio of the students at New Mexico State University (NMSU), and a simple coin flip.

“In 1962, I had just spent nearly five years in the U.S. Air Force stationed at a base on the northern tip of Maine, and I was ready to get out of there and go to college,” Tony, now 76, explains. “It would start snowing in September and the ice would finally melt in the lakes in May. I knew I wanted to go to school somewhere warm! That was my criteria. So I applied to schools in a crescent from Miami to Phoenix and investigated important stuff like the male-to-female ratio. I narrowed it down to two schools, flipped a coin, and ended up at NMSU. I didn’t know a single soul in New Mexico.”

Raised in heavily wooded North Central Pennsylvania, Tony was an avid hunter, fisherman, and trapper, but had no idea what his college major might be.

“At freshman orientation, I learned that NMSU had a school of agriculture,” he recalls. “Well, I always kind of liked farming, so I checked it out and discovered there was a wildlife management curriculum. I liked to hunt and fish even more than farming, so it was an easy choice.”

By 1966, Tony had not only earned his degree in wildlife management, but also the notice of the New Mexico Department of Game and Fish. He was quickly hired as an Information and Education officer.

“It was kind of a unique set-up, because everybody there was a law enforcement officer,” he says. “There weren’t that many employees, so we all had to do everything. I can remember being with my good buddy, John Mechler, and chasing bad guys down gravel roads at night, high speed with no headlights. Crazy stuff! You could never do that sort of thing today.”

In addition to chasing “bad guys,” Tony was gaining valuable, real-world experience in wildlife management.

“I worked quite a while on a deer project that addressed poor fawn ratio,” he says. “For some reason, the majority of the fawns in southwest New Mexico were dying. Eventually, I determined that a lot of it had to do with fire control. Most of the forests had been allowed to grow up and there wasn’t any green feed, and it’s critical for deer fawns to have succulent young vegetation for vitamin A and E. If they don’t have access to it, they get something called white muscle disease. It was an interesting project, but I learned a valuable lesson: You have to have public support to get things accomplished, and we didn’t really have it. By the early ’70s, I was ready to try something else.”

As if on cue, fate took another turn for Tony when his friend, John Mechler, ended up in Tennessee.

“He got a job with the TVA [Tennessee Valley Authority] and moved away,” Tony says. “We talked on the phone every so often, and he called me out of the blue one day and said, ‘Campbell, I’ve got the perfect job for you! The Tennessee Conservation League is going to hire their first employee.’”

After a series of interviews, 33-year-old Tony found himself holding the keys to the future of wildlife conservation in Tennessee.

“I came here in May of 1972,” says Tony. “They paid me a great salary—$12,000 a year! I was in hog heaven and had no idea what I was doing!”

As a young man with only a few years experience in wildlife management and none at all in Tennessee, Tony would become the “point of the spear” for natural resource public policy and a legend among the movers and shakers of the conservation movement in the Volunteer State. Tennessee Out-Of-Doors recently visited with Tony in the tiny Nashville bedroom community of Kingston Springs, where he has served as mayor for the past 16 years.

OOD: When you started at TCL, you were still very young in your career. What was it like walking into a well-established, completely volunteer organization as a 33 year-old, a new Tennessean, and the only staffer?

TC: It was scary. I was just a young whippersnapper, I had no idea what I was getting myself into, and I think I was just too ignorant to be overwhelmed. The TCL president at the time, Dr. Greer Ricketson, helped me get a small office down at the Mid-State Medical Center. There was a little bit of office equipment at the secretary’s house in Johnson City, but not much.

OOD: Did the TCL Board of Directors ease you into the position slowly or throw you in headfirst?

TC: They threw me in. I walked in there and the board of directors immediately tasked me with two projects: matching a $100,000 grant from the Meeman Foundation in Memphis over three years, and diversifying the organization by recruiting black members. Looking back on it, I really have no idea how I did either, but somehow I did. I had absolutely no experience in fundraising, so that really kept me up at nights. I had to develop my own relationships, too. We ended up working with the Nashville Sportsmen’s Club, which was a black group. Their president at the time, Mitchell Parks, is still a good friend of mine today.

OOD: Did you find that you had some natural talents that surprised you?

TC: Yes, I think I was best at public policy and bringing people together. That’s how the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency came about, in large part. I hadn’t been at TCL very long when Ed Thaxton, Gov. Winfield Dunn’s environmental advisor, came to my office and told me there were problems with the Tennessee Game and Fish Commission and asked for my help. At that time, you had the Law Enforcement Division, the Fisheries Division, and the Wildlife Division, and they fought each other tooth and toenail. I recommended that we put together a panel of nationally known experts to come evaluate the agency, see how it could be more responsive to the public, etc. The governor thought that was a good idea and that’s what we did. The panel recommended changing the whole structure and requiring officers to have a college degree in wildlife and making them multipurpose by having them do wildlife management, fisheries, public relations, and the whole spectrum of things. I helped get the legislation passed and that became TWRA.

OOD: What was the level of interest in conservation at the state capital in the 1970’s and ’80’s? Was it more difficult to get things done?

TC: I think it was, yes. There was an education process. [Former Gov. Lamar] Alexander and [former Gov. Ned] McWherter were supportive. The Blanton Administration wasn’t. We had good relations with Winfield Dunn. In my opinion, McWherter was far and away the most effective in terms of getting things accomplished, especially in relation to wetlands conservation. For example, there was an ongoing debate over the route of a new highway being built between Jackson and Dyersburg. McWherter’s secretary called me one day and said, “Tony, he wants you at a meeting at his legislative office this afternoon.” Well, you didn’t say no to that. When I got down there, there was a big argument going on between two legislators because one of them wanted to take the highway through Trenton. One of them turned to McWherter and said, “Tony’s not going to let them do it that way because it’s going to cross all the wetlands, and he’s going to sue us.” McWherter asked me if that was true. I said, “Yes, sir. It doesn’t need to go across all those wetlands.” He said, “Alright. We’ll take it down the ridge.” And that’s the way it went. From then on, I was often consulted on road construction. I think [the Tennessee Department of Transportation] hated to see me show up at their meetings, but we were able to change the attitude towards erosion control on these projects. Those were the days when they were building highways everywhere, and had a heck of a lot of impact on miles and miles of streams.

OOD: In what way?

TC: They were crossing a lot of streams and wetlands, especially in West Tennessee. If they didn’t elevate the road, it screwed things up. Years ago, if you flew over West Tennessee and looked on the upstream side of most of those rivers, there’d be big stands of dead timber. That’s because those crossings weren’t wide enough, and the stream dropped all the silt off on the upstream side and killed the timber. You don’t see that as much anymore, largely due to our efforts.

Tony says conservation in the 1970s and ’80s was largely about developing relationships and educating legislators on the principles of stewardship.

OOD: How was “grassroots” conservation different in those days?

TC: There was a more broad-scale approach back then. I get a little frustrated now with all the species organizations because they take a very narrow view of [conservation]—turkey, trout, whitetail. I’m more comfortable with the old natural resource conservation groups that were out there advocating for everything from quail and rabbits to squirrels, raccoons, bears, and elk. Nearly every town had a sportsmen’s club; East Tennessee was covered with them. But now, society seems to have gone in a different direction. It’s not the “Home Economics Club” anymore. Now, it’s the “Frying Club” and “Crocheting Club” and so on.

OOD: What do you see as the biggest challenge facing sportsmen and women today?

TC: I think it’s the public’s perception of the consumptive use of fish and wildlife, and it goes beyond just that. I think the forestry people are facing the same thing. People have been brainwashed into thinking they shouldn’t cut any trees, but pretty soon, you’re going to lose the red oak component and we won’t have any habitat for deer or turkey. It’s all part of managing.

As far as wildlife goes, we can show that the species that are consumed have much greater populations today than they did 30, 40…even 100 years ago. That’s because we’ve managed them.

OOD: What do you consider your greatest accomplishments over your 23 years with TCL?

TC: Definitely helping with the establishment of TWRA would be one. And I’m very proud of the Wetlands Acquisition Act, which has secured—and continues to secure—many thousands of acres of valuable habitat for waterfowl. That was probably the most significant thing we did in the 1980s.

I’m proud of our involvement in Project CENTS, which stood for Conservation Education Now for Tennessee Students. That was a curriculum that went into all the schools across the state to promote conservation. Hundreds of teachers were trained on it and I’d like to think that it’s still having an impact.

I would also mention our involvement in creating a long-standing group called the Resource Agency Coordinating Committee. This was composed of the heads of agencies like the U.S. Corps of Engineers, TWRA, TVA, and so on. They were constantly bickering, so I saw the need to go off to a state park for a couple days and just hash it out. We actually had a constitution that stated that anything said in that meeting could go nowhere else, and guess what—we got a lot of nifty things done. We all got to know each other, sat down and broke bread, and just talked. We brought people together for the common good.

I would say that in my day, TCL played a big role in creating a professional approach to natural resources conservation from the standpoint of the state. I think the efforts we put forth then are paying dividends today, and for that, I’m proud and grateful.